Woke up at around eleven o’clock in the middle of last night’s snowstorm to a sound that it took me a minute to identify: silence. Twelve years ago Layla introduced me to the practice of sleeping with a fan, or white noise machine, or really anything capable of blanketing us thoroughly. This being pre-kids, I still slept like a normal or at least normal-ish human being, and so adapted to it - adapted so thoroughly, as last night demonstrated, that the abnormal interruptions occasioned by, say, three-quarters of a foot of wet snow congealing to every...single...surface has the power to actually reach over the barrier between sleeping and waking and pull me out, or back in I guess. Like a rabbit being sucked back into its original hat.

This morning I think about it, as the neighbors and I all work our little plots of driveway with those modern New English equivalents of the original ox and plow, the snowblower. Noise is individual; but silence is communal, shared. That’s what makes it difficult to sleep in, to take for granted - at least if you’re not used to it. We are all in it, together, like children huddled in the same cave. So, listening to my wife breathe in the darkness, I can tell that she’s awake too. I can hear everybody, it seems, lying in the dark of our common power-out, listening to the listening.

*

Two writers I’ve been abed with recently come to mind on the topic of silence. The first is somewhat obvious. As a sculptor of prose, Penelope Fitzgerald is pretty much unbeatable, not because her sentences are superb (although they are), but because, reading one of her chapters, or pages, I begin to realize that, really, novels aren’t made out language - or at least not any more than the David, for example, is made out of a mountain. Language is the space that a novel occupies, it’s ground; but the novel itself, that is, the part of the imaginative experience that the reader and writer inhabit together, listening and whispering to one another, like kindergarteners trading nursery rhymes, is the space that language creates: the empty place that it points to, sometimes subtly, sometimes insistently, and sometimes (Fitzgerald is like this) with a schoolmarmish eyebrow raise. Knausgaard:

“Literature is not primarily a place for truths, it is the space where truths play out. For the answer to the question - that I write because I am going to die - to have the intended effect, for it to strike one as truth, a space must first be created in which it can be said. That is what writing is: creating a space in which something can be said.” (Inadvertent, p.8-9)

One would not expect such over-explainer as Karl Ove to enter the mix here, but it is a strange truth of literature, I think, that a writer’s relationship to silence does not necessarily have anything to do with the amount of words she uses. It’s more about the cut - the amount that is left, not behind but on the table, between us, for us. Like an inexhaustible meal, or a battery, a current that must run, if it does, in the space between points. One way I like to get a handle on this in Fitzgerald’s work is the descriptions of people. These descriptions, for the most part, do not exist - but then how are the people there: how does the reader see them, says the MFA lizard-brain? Well, weirdly, by not seeing them, or by seeing them in action, or from the barest glimpse - the way a classical Chinese painting can make you see an entire landscape from a dripping branch.

“She was in appearance small, wispy and wiry, somewhat insignificant from the front view, and totally so from the back. She was not much talked about, not even in Hardborough, where everyone could be seen coming over the wide distances and everything seen was discussed. She made small seasonal changes in what she wore. Everybody knew her winter coat, which was the kind that might just be made to last another year.” (The Bookshop, p.8)

Spare, Defoe-like, and yet plaintive as Chekhov, this is the “everybody knows” of fiction - an everybody that is Fitzgerald’s whole project. We are the everybody.

*

And yet there is so much snow to shovel, so much sheer wadded bulk to move from its current, blocking position to a different one, imperceptibly-torqued perhaps but then flooding us with so much sudden light and meaning that sometimes I feel that silence really is better served, in a weird and totally paradoxical way, by the maximalists. Or, because the term doesn’t really mean anything, by those writers for whom the shovelling is more the point than the finished sculpture, and who therefore do not skimp on showing their work. Here is Donald Phelps describing the “two cardinal images”, of transformation and fighting, used by the comic-book artist E.C. Segar, who invented Popeye in his long-running strip Thimble Theater:

“These two sets of images, dream-like transformation and bloody melee, share a common importance to Thimble Theater: the twin source of that gravity which converts humor into comedy, by investing it with the undertow of the world, and what Kafka called the weight of our own bodies. They represent the habitation within the world-at-large which, in the most notable comedy, and much other art, the imagination makes of itself. And their extremity, winging toward the poles of legerdemain and the savage sculpture of fight-to-the-finish, set off, by contrast, the marvelous kind of seriousness, the sense of reality being hard-by, which informs Thimble Theater through its thirty-six short seasons under Elzie Crysler Segar. Without my memories of such scenes, I could almost believe in the successful film adaptation.” (Reading the Funnies, p.41)

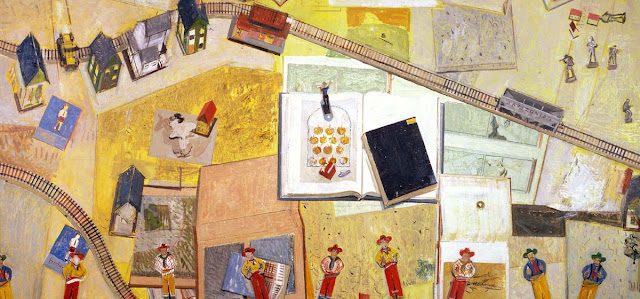

Here and again, and again in his essays, Phelps appears to want to say everything - and yet in a weird way, I find myself constantly feeling as I’m reading him that he is talking around something, a secret that he is leaving sitting there, as if his entire project were some sort of gigantic figure he were trampling in a lonely corn-field. He is respecting something, he cannot say it, and he knows he can’t say it, so he keeps saying, coming close but never hitting it directly. In this way he reminds me of Montaigne, which is to say that he reminds me of all the great essayists, up to and including Phelps’s own idol Manny Farber, who painted what was there as an accretion, rather than refutation, of what was not. A voice in the silence, which I guess is a way of saying a voice of silence. All of ours.

No comments:

Post a Comment