Icy, sodden snowbanks jigsawing around Farmington, making “outside” something the boys and I have to make it a point to do. But that’s the beauty of childhood, at least for an adult: all you’ve got to do is sit in dissatisfaction for a few minutes, and inevitably their attention begins to build, like bacteria in a petri dish, plumping into individual forts that then add battlements, and connect, until eventually you’re bombarding Bunker Hill. In his “Prayer for my Daughter”, Yeats remembers this world:

“Considering that, all hatred driven hence,

The soul recovers radical innocence

And learns at last that it is self-delighting,

Self-appeasing, self-affrighting,

And that its own sweet will is Heaven’s will...”

That’s the dream, right? The Rousseauian wager, in which all we have to do is get rid of all this stuff (civilization to Rousseau, “hatred” to Yeats, material possessions to my parents and, who knows, maybe “distraction” to my generation), in order for the soul to return to something so pure and joyful that we recognize it as, if not heaven itself, then as close to heaven as we can get in a fallen world.

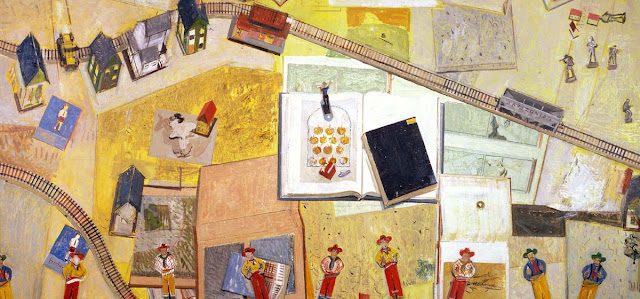

How much are we willing to sacrifice for this dream? Penelope Fitzgerald begins her novel innocence (punctuation from the Mariner edition cover, though the title page has it as Innocence) with a historical parable. The Ridolfis, a family of 16th century Italian midgets, creates a sort of enclosed garden, in which their only daughter, who is also a midget, might grow up without having to encounter the scorn of the outside world. Everything in this preserve is miniaturized, so as to give the young woman the illusion that she and her family are the same height as everyone else. At one point, the Ridolfis are able to acquire a young orphan named Gemma - who is also a midget - from a nearby town, to be a companion for their daughter. The problem of loneliness seems to be solved, for the girl is deaf and dumb and therefore the perfect playmate for a someone who is not allowed to hear anything about the outside world; but then twelve months or so, an unexpected thing happens: Gemma begins to grow! FItzgerald does not hold back:

“Meanwhile Gemma had taken to going up and down the wrong steps in the garden, the old flights of giant [i.e. “normal-sized”] steps which had been left here and there and should have been used only for occasional games. The little Rudolfi made a special intention, and prayed to be shown the way out of her difficulties. In a few weeks an answer suggested itself. Since Gemma must never know the increasing difference between herself and the rest of the world, she would be better off if she was blind - happier, that is, if her eyes were put out. And since there seemed no other way to stop her going up and down the wrong staircases, it would be better for her, surely, in the long run, if her legs were cut off at the knee.” (Innocence, p. 10-11)

*

“The sustenance of the comic strip is sheer continuity, the endurance of its daily, hypnotic present tense.” (204) So says Donald Phelps, in his majestic, terribly-edited (I found at least two-dozen typos and misspellings) Reading the Funnies. The book raises the question (among others) of what an “innocent” art might look like, since certainly it can’t look like me and my sons throwing snowballs. Figuring this out requires a certain amount of overlaying, since Phelps’s knotting, thinking-out-loud style rarely says things directly, at least not without immediately taking that direct statement as a starting point for another flight (echoes of Mandelstam’s metaphor for poetry as an airplane that somehow, mid-flight, builds another airplane). Still, two ideas I took from the book were, first, the consecration of day to day, “ordinary” life as a vital part of the greatest comic strips’ achievements, and two, the existence of style in these achievements as a sort of continual reckoning, “a device for keeping faith with the world, even as he keeps it at bay.” (p. 123 - this is Phelps on Harrison Cady’s style particularly). Both ideas are compelling to me, and seem to ring off Fitgerald insofar as they suggest the obvious: that is, that at the end of the day there is no innocent art, although there may be an art of innocence. An art about innocence - an art that wants to think about how “innocence”, such as it is, can be indicated, if only by pointing at the place where it would be, if we were really innocent. For Phelps, so far as I understand him, the American comics of the ‘30s and ‘40s - for all their frequent corniness, lameness, or just plain incomprehensibility to readers 80-years later - had a unique ability to do this; thus they managed the pretty inconceivable trick of being “Radical” in the Yeatsian sense while still being as ordinary as a walk in the snow. How they did this is one of the fascinating and useful histories that this book maps (one brief example, about Harold Gray, of Little Orphan Annie fame: “The attitude which can be inferred from a comic-strip is the operative factor, or, none at all; and Gray’s attitude, to any one-eyed reader using that single eye with minimal discretion, comprises the most profound (and very far from smug) distrust of even the latitude of the law…”).

Finally Davenport, from that hidden poetics, II Timothy:

“If my writing, involved as it is with allegiances and sensualities, with its animosity towards meanness and smallness, has any redeeming value, it will be in its small vision (and smaller talent) that Christianity is still a force of great strength, imagination, and moral beauty if you can find it despite the churches and dogma.”

For the record, I think he is only almost telling the truth here. He wants to put another word where “Christianity” is, but he either doesn’t know what that word is, or is afraid to use it. And thank god, since using it would very much deplete the power of his beautiful essay - not to mention its truth.